This is going to be a fun article to write (not really), because the concept of gain is actually kind of elusive to define if you’re trying to be general. I’ve always understood the concept of gain as it pertains to guitar pedals (and general guitar oriented analogue electronics). However, as I did some research on this topic to clarify a few points, I was reminded that gain can be seen very differently depending on who you’re talking to.

So, before I begin, I want to clarify that I’m mostly coming at the concept of gain from the perspective of guitar pedals and building your own guitar pedals, especially analogue guitar pedals and analogue sound signals. This won’t mean that my explanation of gain will be wrong when talking about digital sound signals, or when talking about antenna gain (which is a thing I learned about when researching this article), but it may not make as much sense. I’ll try my best to be universal though.

What Is Gain?

Although it comes from an article talking almost exclusively about digital audio, eMastered has a good and concise definition of gain:

“gain is the level of your audio going into a system while the volume is the level going out of your system.”

I like eMastered definition because it’s concise, but it can also be difficult to understand.

My concise answer to the question is: gain is how much a signal has been amplified.

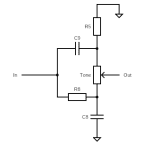

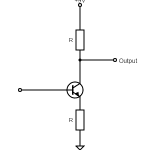

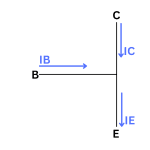

When we’re talking about analogue electronics (like guitar pedals), we’re usually talking about voltage gain. This is the difference between how much voltage goes in versus how much voltage comes out. This is usually in terms of transistor gain (hFE/Beta) or gain from an operational amplifier. The hFE/Beta rating for a transistor doesn’t have any units, it’s just a multiplication factor for how how voltage can be potentially increased. So, if a transistor has an hFE of 50, it will increase voltage by 50 times.

To go deeper into it, consider a signal coming out of an electric guitar. On the lower end, an electric guitar may only let out 100 mV of electricity. This can go all the way up to 1 or even 1.5 V. Let’s say your “typical” electric guitar signal is 300 mV to make things easier. That’s not going to be a strong enough signal to really do anything with. And that’s where gain comes in. Gain amplifies a signal so that “other stuff” can happen to it. That other stuff is generally turning it into changes in air pressure to produce sounds through a speaker. You can adjust how much of that amplified signal is getting to the speakers through the volume.

It’s not as simple as saying that gain brings it up and volume brings it down, but there is some aspect to it, at least in guitar pedals and simple volume knob configurations in analogue electronics – this may be different when you’re talking digital though.

What’s The Point Of Gain

The main point of gain, generally speaking, is to bring signals up to a suitable level.

I’ve already mentioned that an electric guitar’s signal is too low to actually be heard through a speaker, so that signal is amplified to fix that.

This can also be used when recording very loud or very quiet sounds with a microphone.

For example, if you have two actors on a stage whispering, their conversation may need to be amplified a lot (i.e. a lot of gain) to be heard. However, if that conversation turns into a shouting match, there can be too much amplification and then the sound becomes distorted. To learn more about this, read my article on transistor active and saturation regions, but for the quick summary, it has to do with when you put too much voltage into a transistor; and remember, gain is just the difference between the voltage going in and going out.

So going back to our actors on stage, if the scene changes from whispering to shouting, whoever is doing the sound may need to adjust the gain on the microphones in order to avoid distortion from happening.

With this in mind, peaks like this coming from shouting can’t be fixed after the fact. Remember that gain is what’s going into the system. If the voltage going in is too high, it will distort.

How Is Gain Different From Volume?

You may be thinking “gain makes things louder, so it’s just volume,” and it’s a common mistake to make.

To reiterate, gain is about what’s done to a signal going in: it’s amplified, and that amplification amount is called gain. Volume is what happens to the signal coming out. That signal is as big as it’s ever going to be, the volume is just the final adjustment.

Staying with my example of whispering and shouting, gain can also be used to adjust individual signals so that everything comes out the same volume. If you have one person on stage whispering and one person yelling, you can increase the gain of the whisper and/or decrease the gain on the yell while keeping a single volume for volume so they come out the same level.

Now put the example above into a whole band being recorded.

How Gain Affects Tone

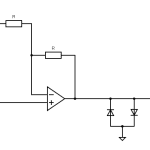

Adjusting the gain on an amplifier can greatly affect what sort of tone is coming through. Higher gain, especially as you’re starting to push towards the saturation region of whatever you’re using to amplify your signal (transistor, op-amp, or even tube), will thicken up a sound.

A lot of the time when you’re looking at a guitar pedal, the gain control knob will affect how much distortion there is, but that’s not always the case. A clean boost pedal, like the ZVEX SHO is just a simple gain circuit that amplifies a signal; it’s basically just a pre-amp. Although the SHO is a transparent boost, I still reckon it fattens up the sound. Different transistors also affect tone in different ways.

Increasing the gain on a signal makes it sound thicker and richer, at least for analogue circuits. Early tube amplifiers would get their full tone when pushed to their limits. This is because the imperfect tubes had the most natural sounds when living up to their full potential. Transistors and op-amps are similar. The minor imperfections are what makes things sound natural and real, and higher gain amplifies these small imperfections. It may only be small, but, like a whisper, higher gain is needed to hear those small sounds.

What About Gain And Distortion/Over Drive Pedals

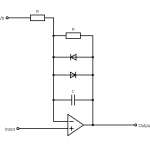

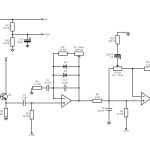

I’ve already mentioned that a lot of overdrive, distortion, and fuzz pedals will have a knob that reads “gain” and use it in place of “drive,” “fuzz,” or “distortion.” To fully appreciate how gain and distortion are related, take a look at my guide to diode clipping in guitar pedals.

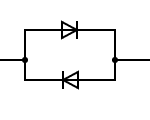

The summarised version of this is that it’s the diodes that create the distorted sounds. Diodes will cause a voltage drop when a signal passes through them. So, first you amplify a signal (gain) then you pass it through a diode causing a specific voltage drop, clipping the signal and causing distortion. As you amplify the signal, a more significant portion of that signal is going to get clipped off, causing it to be more distorted.

So with guitar pedals, you often associate gain with distortion, but it’s often because how that gain is interacting with the diodes in the circuit.

However, to make things more complicated, too much gain can also cause distortion, with or without clipping diodes. This has to do with the saturation point of a transistor, imperfections getting amplified, or simply whether a speaker can take it!

That’s A Lot Of Words To Say That Gain Is Signal Amplification

And it is… but the big thing I’m trying to get across is that gain is different from volume. There’s a lot that can be done with gain and without it, there would be no volume. Volume doesn’t actually increase signal, it just works with the existing signal and allows more or less through.

Gain also isn’t unique to audio signals. It can be used to increase general electrical signals, radio frequencies, and more. That’s out of my area of expertise, but the principles are the same.

Now get out there and build something that makes noise.

Related posts:

What’s The Difference Between Overdrive, Distortion, And Fuzz?

What’s The Difference Between Overdrive, Distortion, And Fuzz?

How To Use A Distortion Or Overdrive Pedal

How To Use A Distortion Or Overdrive Pedal

What’s The Difference Between Symmetrical And Asymmetrical Clipping?

What’s The Difference Between Symmetrical And Asymmetrical Clipping?

Ultimate Guide To Diodes In Guitar Pedals: What They Do And How They Work

Ultimate Guide To Diodes In Guitar Pedals: What They Do And How They Work

Ultimate Guide To Transistors In Guitar Pedals: What They Do And How They Work

Ultimate Guide To Transistors In Guitar Pedals: What They Do And How They Work

Understanding Mid-Scoops And The Big Muff Tone Circuit

Understanding Mid-Scoops And The Big Muff Tone Circuit

How To Find The Audio Signal Path For A Guitar Pedal

How To Find The Audio Signal Path For A Guitar Pedal

What Is Transistor hFE?

What Is Transistor hFE?

Transistor Saturation, Active, And Cutoff Region

Transistor Saturation, Active, And Cutoff Region

Is It Expensive To Make Your Own Guitar Pedals?

Is It Expensive To Make Your Own Guitar Pedals?